The School’s beginning in 1788 was to fill a perceived need. Eighteenth century daughters had a function as a member of a family (sister of/ daughter of) and a purpose to grow into graceful adulthood to become wife of/ mother of. Take that function away and her role pretty much collapsed. So if circumstances caused change, she could not swiftly morph into another. A charity to support the daughters of indigent freemasons provided support because decorative females had no alternative. Supporting the daughter and, by this means, alleviating the financial strain on the mother, was more sensible than ‘handouts’ to the mother because in helping the daughter, you helped all the family. Ovvious, innit?

So began an institution in which daughters in need would be placed. But it brought with it the question – what do you do with them when they are there? Providing them with an education would occupy their time and would stand them in good stead perhaps should Mr Right not come along at an appropriate time, and would return them to their family in a better position than when they left it.

Right. Good. Now the crunch. What sort of education? Females were unlikely to have to earn a living for long. Women only worked by necessity so an education, for example, drawn from the seven liberal arts – as might be the case in a boys’ grammar school – would be well beyond requirements. At the same time, it did not seem appropriate to provide the sort of lessons given to upper class daughters: painting, fine embroidery, singing, dancing or the art of conversation. These were the daughters of middle class families. What need of music? So their education was basic. Reading, writing, enough knowledge of ‘accompts’ for them to run a household efficiently and their catechism. Oh yes, and sewing – just plain sewing, running repairs, darning, creating and maintaining household napiery, and so on. All the things that nobody can do any more. When the School had a 1934 day to celebrate 75 years on its present site, it was felt that asking the girls to come in full 1934 costume was probably pushing it for just one day but perhaps a pinafore (part of the uniform still in 1934) as a token would suffice? That was when it was discovered that mummies didn’t sew any more as the School fielded not a few cris des coeurs over the summer holidays from parents asking how to make a pinafore. They turned out alright in the end. And the staff had the most enormous fun finding costumes and playing their 1934 counterparts!

But back to earlier days. The business of education was a serious matter but still basic. It met needs and that was sufficient. In 1848 – 60 years later – a move to add some extras in the form of music lessons and French was rejected firmly as unrequired.

However, the idea had been set free so it is hardly surprising that, ten years later, music and French were both added and the first of many, many pianos over the years was supplied to the school.

All of this is a contrived preface to the idea that music, once thought of a mere frivolity, became such a staple that, by the end of the C19th, probably most of the pupils could find their way round a piano keyboard and chirp beautifully either as soloists or in choirs. And some were able to turn it into a career.

The scene is set to introduce Mildred Wrighton as an exemplar of musical ability. She wasn’t the only one so selecting her is merely a token but as she appeared in a great number of newspaper articles, all extolling her performing abilities, there is a lot of material to use.

Mildred Ammon Wrighton was born in 1874. Her father, William Thomas Wrighton, could be described as a man with daughters. He married twice: his first marriage produced five daughters and then he married Emily Martin Warren. They had a further 3 daughters including Mildred. In 1869, William was given as Professor of Singing. This label ‘professor’ was used in a way we would not do today where a professor is linked to a university chair and is the ultimate status in academe. In Victorian times, both men and women used the term professor without having gone anywhere near a university. Quite what the difference was between a teacher of music and a professor of music has been lost to us since none of them appear to have much in the way of official qualifications. In William Wrighton’s case, he was also a composer. He wrote mainly piano music, including ‘The dearest spot’, ‘Her bright smile haunts me still’ and ‘She sang among the flowers’.

No. No idea.

Apparently you can still buy and download ‘Her bright smile haunts me still’ should you be so inclined.

This is Papa Wrighton in his prime. He would have been 40 years of age when this was published. However, with such a large family, perhaps music was insufficiently remunerative. When he died in 1880, his probate describes him as a composer of music but late licensed victualler of Hotel Mount Ephraim, Tunbridge Wells. Mount Ephraim is an area of Tunbridge Wells so it is hard to pinpoint if this hotel still exists today just renamed or if it has disappeared. There is a possibility that it is now the Spa Hotel or the Royal Wells or even Mount Edgcumbe Hotel. Or maybe none of the above. His widow took over the premises after her husband’s death and in 1881 Mildred is there with her.

Shortly afterwards, Mildred became a pupil at RMIG where she remained until June 1890. Her valedictory report says this of her:

‘has always been a good girl and is a prefect. She has only made fair progress in her studies generally but excels in music being a good player for which she took a prize this year.’

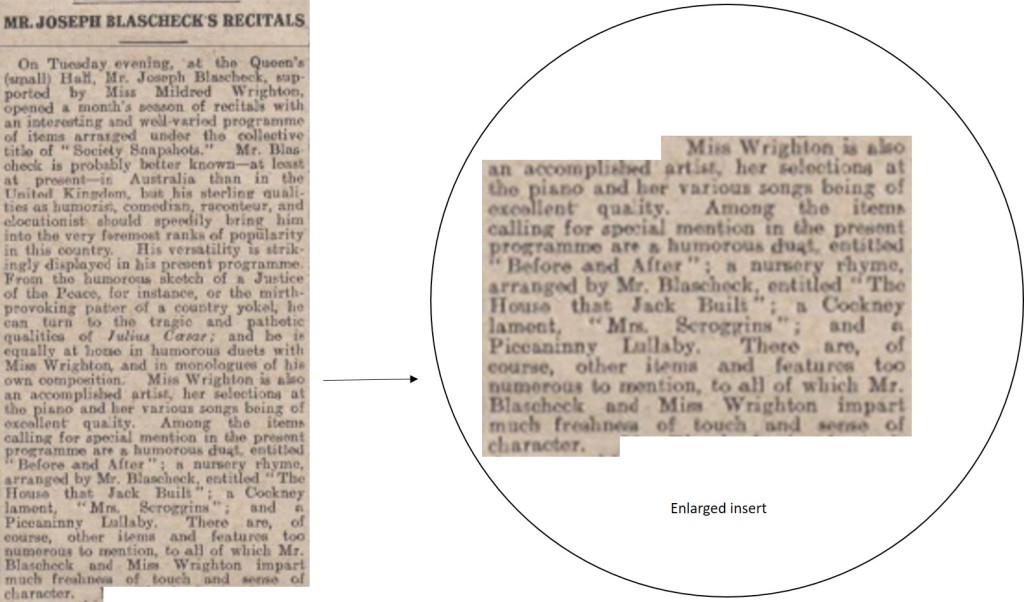

Rather like the apocryphal comment made about Fred Astaire’s screen test (Can’t act. Can’t sing. Can dance a little), the Head Governess’ comment notes Mildred’s talent whilst at the same time belittling it. There is the unspoken view that musical talent was not going to get her very far whereas attention to her lessons would. How wrong can you be? Mildred went on to be a great success on the musical stage. In 1907, for example, the following was written of her:

Five years later, she was still earning plaudits.

In the early 1900s, Mildred was a singer at many entertainments. All of the newspaper references (about 200 of them!) praise her ability, her voice and her role as humorist’s assistant. She was clearly popular. In Chichester in 1913, for example, it was written

And within that comment is the fact that she took after Papa and was composing her own material. Her talents reached beyond UK shores too as there are reports of performances in New Zealand and Australia. Her co-performer, Joseph Blascheck, was Australian so perhaps he was instrumental in arranging this.

Just as a by the bye, Joseph Blascheck was married to Beatrice Pewtress, reputed daughter of Ellen Terry and their son became an actor taking the name Ballard Berkeley. He played, among many other roles, Major Gowen, resident of Fawlty Towers.

Perhaps during her antipodean theatre tour, Mildred met William Farquhar Young. After his first wife died in February 1915, Mildred and William married the following year in St Paul’s Presbyterian Church.

Without ready access to all New Zealand newspapers, it is not possible to say if Mildred went on performing but her husband had repute as a fine singer with ‘one of the loveliest speaking voices I have ever heard’ (the editor of Triad, cited in the Cyclopedia of New Zealand [Otago & Southland provincial districts] http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-Cyc04Cycl-t1-body1-d2-d22-d5.html). Mr Young was ‘well known as a bass singer and elocutionist throughout New Zealand’ (ibid) and had appeared on stage since he was a boy. His first adult appearance was in 1885 ‘as the sergeant of police in the “Pirates of Penzance”; his rendering of the part was a brilliant success’ (ibid). He toured successfully and perhaps this is where he and Mildred crossed paths.

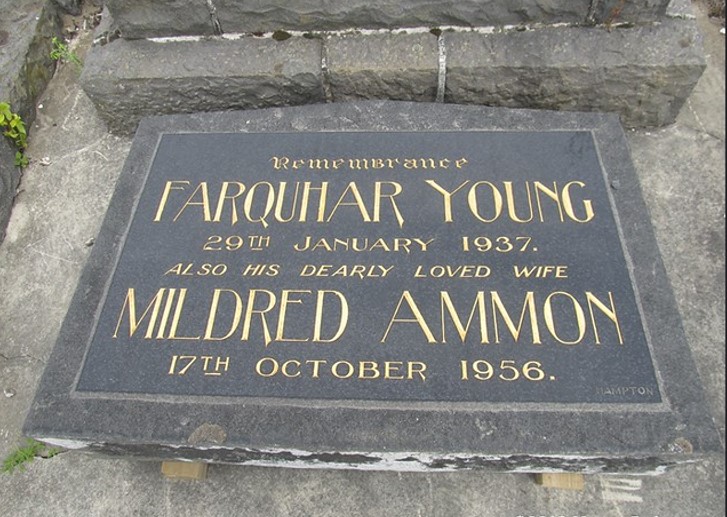

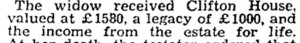

After their marriage, Mildred made New Zealand her home. When William died in 1937,

In the 1949 electoral roll, she is listed at 29 Cheltenham St, Christchurch, Canterbury, NZ. She died in Christchurch in 1956, aged 82 and is buried in Bromley cemetery there.

Mildred’s success as a songbird may have been somewhat greater than her final report might indicate. A career in light entertainment which spanned the globe seems a bit more than ‘only fair progress’ – the equivalent of ‘C+ could do better’. Mildred appears to have been a chip off the old block and her father, if he had known of her success, would no doubt have been very proud of her. Her prize for music in about 1889 seems to have stood her in good stead.