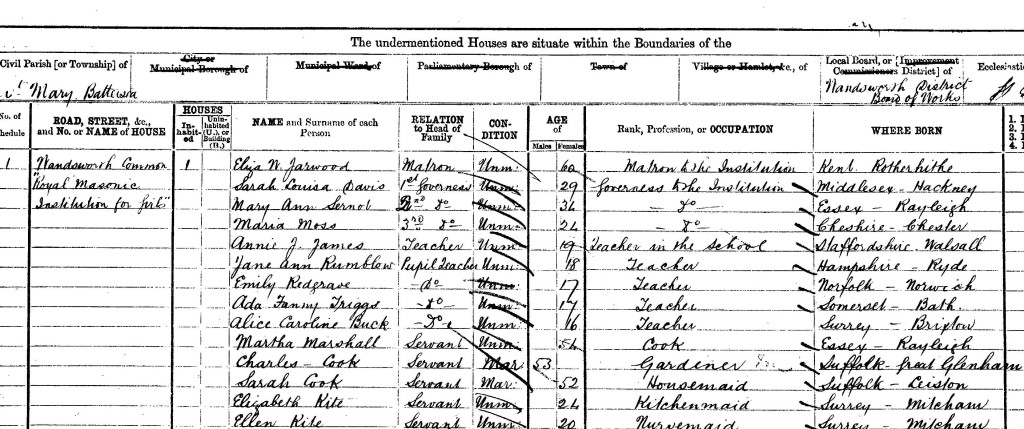

Those familiar with any aspect of the School’s history will also be familiar with the names Eliza Waterman Jarwood and Bertha Jane Dean, long-serving matron and revered Headteacher respectively.

Their lives, greatly dominated by their time at the School, are well recorded. But what is less well known is that both had sisters who were also pupils at the School. Despite the ruling about no sisters being allowed, this rule waxed and waned over the years and there are many instances of sisters amongst the School population. Time to try and bring these particular lesser-known sisters out of the shadows. One has to use the verb ‘try’ as, in the case of Sarah Jarwood, so little is known that she almost becomes a figment of imagination.

Eliza and Sarah were daughters of John Jarwood (often written as Jerwood), a master mariner, and his wife Nancy Waterman. John died in 1818 – date unknown but his will of 1815 was proved in August 1818 so his death must have occurred by then. Furthermore, his youngest child was born in February 1819 so the death cannot have been earlier than May 1818. John must have died between May and August of 1818. By this will, he appointed his wife Nancy as his sole executrix.

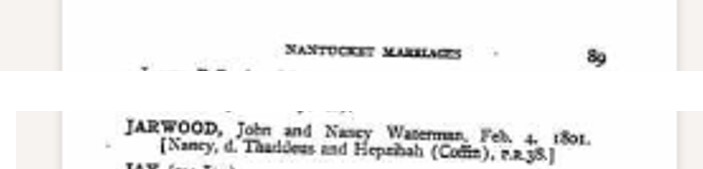

Nancy was originally from Nantucket, Massachusetts so it seems possible that John and Nancy met in Nantucket when John landed there from an Atlantic crossing. Nantucket was particularly renowned for whale oil trade but whether this was the trade the ship John captained is an unknown element.

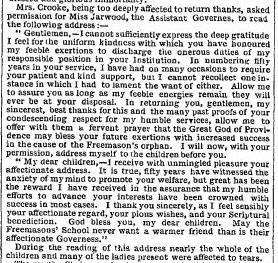

The couple were married in 1801 in Nantucket, a fact which was later to cause a problem with the admission of Eliza to the School. John’s death left Nancy unsupported and pregnant with their fifth child. Furthermore, the family were living in Cherry Garden Street, Bermondsey so Nancy was on the other side of a large ocean from her own family support. As John had been a member of the Royal Naval Lodge, his children became eligible for admission to the School. However, the documentation required for a petition included a marriage certificate of the parents and, because the marriage had taken place in America, this was not available. Nancy had to provide other ‘proof’ that she and John had indeed been married, which proof included a sworn statement by another Nantuckian, also married to an Englishman and living in Bermondsey. It would appear the Atlantic trade was not just in oil but in American brides! This sufficed and Eliza was duly admitted on 21 Oct 1819.

Sarah was the fourth child of the Jarwoods, born on 16 April 1817 and baptised in May at St Mary’s, Rotherhithe.

There is no indication that her petition encountered the same difficulties as Eliza’s had so presumably, having proved the marriage to be valid once, it was not necessary to prove it again. Sarah was admitted on 19 April 1827 by which point her older sister had already been apprenticed to the School and embarked on her long career. Although they were both at the School at the same time, they were not pupils at the same time. In 1832 Sarah left, delivered to her mother. What she did then is not recorded. However, in the 1841 census at the School, there is a Sarah Jarwood or Yarwood listed of approximately the right age which may well have been the younger sister of Eliza. Unfortunately, there is no further trace of her in any census returns. Upon Eliza’s death in 1886, Sarah is given as a spinster and sole executrix with an address in South Norwood (Whitehorse Lane). This would imply that she was alive at this time but she is not found in any census returns even close to this date. This is unlikely to mean that she avoided registration but that her name may have been misrecorded or badly written making it impossible to locate her. Jarwood, Yarwood, Jerwood? Or something else similar but not the same? This is doubly unfortunate as later returns gave other details such as occupation where relevant. It seems possible that hers is the death recorded in Croydon in 1893 although the birth year is given as 1815 but this is all ifs and buts and maybes. Lesser known indeed.

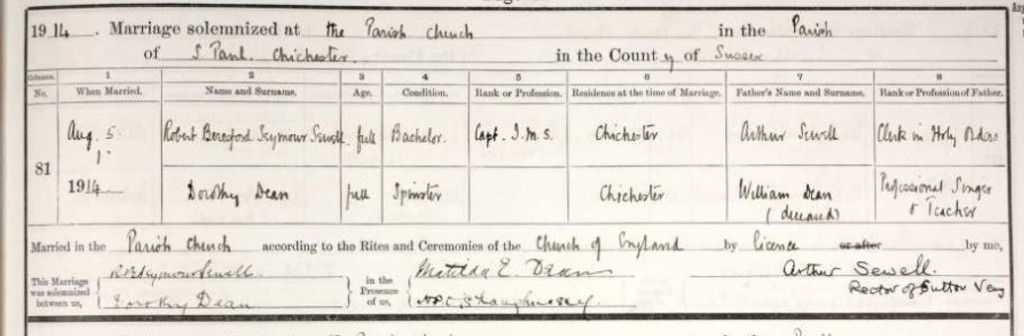

Let us turn now to the Dean family. Bertha and Dorothy Dean were two of the eight children of William and Matilda Dean. The family lived in Chichester where William was a music seller and lay vicar.

His death meant that Matilda had to take over the business as well as be head of the family.

Bertha was admitted to the School in 1887 and from that day forward is always recorded in census returns for the School. Dorothy, five years younger than Bertha, was with her mother in the 1891, 1901 and 1911 census and, bar some fleeting school records, we might not know she had been a pupil. In 1894, she played the piano on Prize Day as part of Trio, the music being ‘Rondo Burlesco’. Trio was a long standing School tradition where eight pianos were played each by three girls at the same time. It was a tradition maintained into the 21st century but, regrettably, no longer a part of the Prize Day concert.

.Dorothy was due to leave in June 1899 and in that year she not only became Silver Medallist but also was confirmed at St Mary’s Battersea. She was retained as a pupil teacher in the junior school, a sort of apprenticeship scheme for any girls showing an inclination towards teaching. In 1900, Dorothy left to take up a daily post in Chichester and in the 1901 and 1911 census returns she is recorded as being a private governess whilst living in North St, Chichester.

In 1914, the day after World War One was declared (Aug 4th), she was married at St Paul’s Chichester.

Her bridegroom was at the time a serving officer in the Indian Medical Service (commissioned into the IMS in 1908) and he was recalled to duty the next day. According to the Cambridge Alumni, he served in Aden and Palestine. A graduate of Christ’s, he gained a 1st class degree in Natural Sciences and was Surgeon-Naturalist to the Marine Survey of India. Later he described himself as zoologist, oceanographer and research scientist. His first positions in India were as medical officer with the 67th and 84th Punjabi Regiments before working as a malaria officer in the Sialkote Brigade.

Dorothy may have already visited India before she was married as Massonica 1912 records her address as Hampton, Conoor, Nilgiris, Southern India. However, this was then crossed through without further explanation and in 1914 she was recorded as being governess to a private family in Luton. It is possible that she had been a private governess in India and that this is where she met her future husband although this has to remain firmly in Speculationland. After her marriage, Dorothy must have gone [back] to India as the couple’s first daughter was born in Coonoor in 1916 with a second daughter in 1919 (also in Coonoor). By this time, Dorothy’s sister Bertha had become head teacher of a girls’ school in London which must have seemed a long way away.

It is interesting to note at this juncture, as a by the bye, that the great-aunt of Robert Beresford Seymour Sewell (Dorothy’s husband) had been a pioneer in girls’ education. Elizabeth Missing Sewell (1815-1906) ‘convinced that middle-class girls needed a better education’ founded Ventnor St Boniface School. ‘Its many years of prosperity were gradually curbed by the high schools that came into being in 1872’ (from Wikipedia). She defined her methods of education in Principles of Education, drawn from Nature and Revelation, and applied to Female Education in the Upper Classes (1865) – they liked long titles then.

Leaping forward to the next generation, Dorothy’s daughter Elizabeth went to Cambridge, graduating in 1942. She then worked for the Ministry of Education until the end of the war whereupon she returned to Cambridge for her PhD. She became a professor and held several fellowships in America where she became a US citizen in 1973. She ‘often wrote about the connections between science and literature’ (from Wikipedia).

Before his retirement in 1935, Dorothy’s husband was Leader of the John Murray expedition, 1933-4 which travelled through the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden, the north-western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Oman collecting data and material which formed the basis of a long series of reports published by the British Museum (Natural History) over a period of more than 30 years. The Indian Ocean at the time was the least studied oceanic area on earth, having been entirely missed or visited only briefly by ail of the major oceanographic expeditions. (Extracted from Oceanologica Acta 1984 – vol. 7 – N” 1)

Sadly, by this time, Dorothy had died.

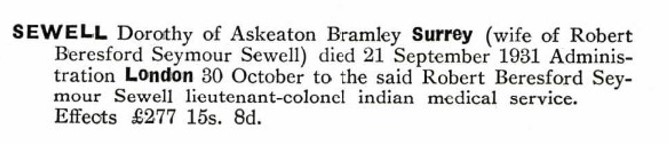

It is an indication of her shadowy existence that we not only know so little about her personally (although we know considerably more about other members of her family) but that her probate has more about her husband than herself.

Whilst Dorothy Sewell nee Dean and Sarah Jarwood must both have had personal histories, they remain as the lesser known sisters of women known well to the School’s history.