Previously, the focus was upon the coaching inn and its connection to Mary Simpson. Now we turn to Mary 2 – Mary Ann Skudder – and her association with mail delivery.

Mary Ann was born in Great Yarmouth, described in Great Expectations by Peggotty as the ‘finest place in the universe’, and baptised in the same church in which her parents married, now designated a minster church and possibly the oldest building in Great Yarmouth.

http://www.photosofchurches.com/norfolk-great-yarmouth-church.htm

Mary Ann’s father, John, married Elizabeth Fleming on 10 June 1798 and is recorded in Lane’s Masonic Records as being a mail coachman.Whilst there is an outside possibility that he visited The Swan with Two Necks, ‘Aldgate was the general starting point and terminus for all East Anglian coaches.’ This perhaps suggests that it is unlikely that James Simpson and John Skudder met in the course of their employment. (http://www.mynorwich.co.uk/harleston-stage-coaches-and-carriers/)

Coachman were not postal employees but hired by the inns at which the coaches arrived. They were famous for their driving ability, so famous in fact that gentlemen adopted the coachman’s dress style rather than the other way around (working people mimicking gentlemen).

They wore a drab great coat that might have many short capes layered at the shoulders to lead rain away from their bodies and provide under layers that were not readily wet through. They wore a spotted Belcher handkerchief instead of a cravat, a tall beaver hat, striped waistcoat, white corduroy breeches, and boots. A coachman carried a whip with which he was said to be so expert that he could flick flies off his horses without startling them.

http://www.georgianindex.net/R_mail/coach/rm_driver.html

The mail coach is believed to been the brain child of John Palmer. He certainly made his fortune from them! The first designated mail coach was in 1784. Before this, letters had been carried to their destinations by a horse and rider but it was a system riddled with problems:

Over-ridden horses fell lame or ill, the temptation to linger with a mug of beer over the ale-house fire was too great to be resisted, on lonely country roads the boys were sometimes set upon and robbed. So many letters never reached their destination that correspondents hesitated to use the post

http://www.ourcivilisation.com/smartboard/shop/bynpwllr/coaches2.htm

In 1784, Palmer advertised that the coach Diligence would convey the mail with an armed guard for protection and could also carry four passengers. Beginning on August 2nd, it

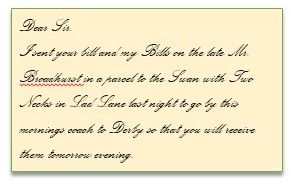

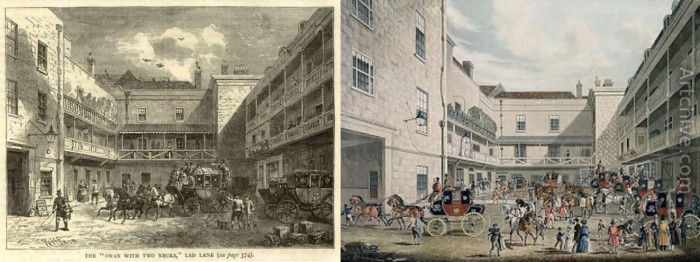

will set off every Night at Eight o’clock from the Swan with Two Necks Lad’s Lane London, and arrive at the Three Tuns Inn Bath before Ten the next Morning

The price for passengers was twenty-eight shillings and, perhaps aware of the previously poor reputation of coachman

Both the Guard and the Coachman … have given ample security to the Proprietors for their conduct, so that those Ladies and Gentlemen, who may be pleased to honour them with their Encouragement, may depend upon every Respect and Attention.

The terror of road travel at the time was the highwayman but second to him was the mail guard! Rosamond Bayne-Powell in Travellers in Eighteenth-Century England cites Pennant (1792): ‘these guards shoot at dogs, hogs, sheep and poultry as they pass the road, and even in towns to the great terror and danger of the inhabitants’ http://www.ourcivilisation.com/

Coachmen supplemented their low wages in tips for carrying mail, undercutting the official charges. On good routes, income could rise from 12s per week (for the night coach, best to be avoided) to £400-£500 annual income. These were the ‘kings’ of the road. ‘The men who drove the mail-coaches were a brave, hardy race, many of them great characters.’ One of them, William Salter, drove the Yarmouth stage-coach (no dates cited so not possible to know if he were contemporaneous with John Skudder); part of his epitaph reads:

Here lies Will Salter, honest man

Deny it Envy if you can

True to his Business and his Trust

Always punctual, always just …

The coach called The Star ‘started from Yarmouth, [and] was the only coach stopping at Harleston that went on all the way to London without passengers having to change to another coach.’ http://www.mynorwich.co.uk/harleston-stage-coaches-and-carriers/ (Again, no dates cited so impossible to say if this were the coach on which Skudder was coachman.) A German traveller, J. H. Campe, found his journey from Great Yarmouth to London a ‘veritable torture’. http://wordwenches.typepad.com/word_wenches/2015/03/travelling-the-roads-of-regency-england-with-louise-allen.html [no date given but early 1800s]

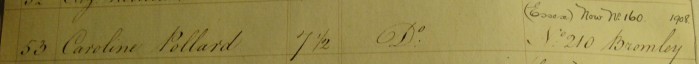

Whether John Skudder was a ’king of the road’ or one of the poor earners is unknown but when his daughter was admitted to the School, the home address given was Eagle Assurance office which rather sounds as if he had perhaps changed occupation.

However, a direct descendant of John Skudder later pointed out that ‘On the 22nd of April 1802 he was made a Mason in the United Grand Lodge of England, his occupation shown as Mail Coachman. His age is given as 32’. Seven years later, when he died (in 1809) his age was given as 49. He was buried in Great Yarmouth on the 18th June 1809. Mary Ann was admitted to the School in 1810 which fits with the death of her father but it does not explain why the ‘family’ address given in the School registers is the Eagle Assurance office. It seems unlikely that this little mystery will ever be solved!

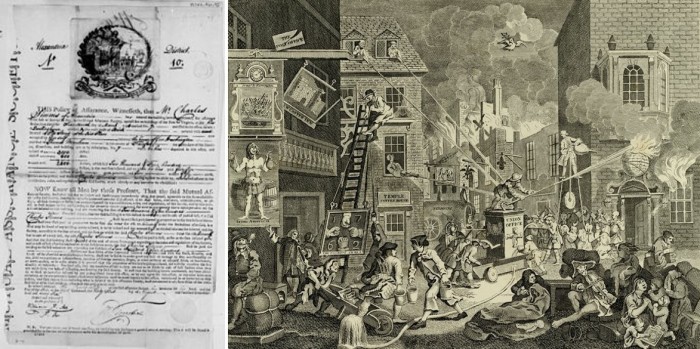

The Eagle Insurance Company was founded in 1807, the purpose being ‘for fire and life assurance and for granting annuities’ and its City office was at 41 Threadneedle Street. (info from http://www.aim25.ac.uk/cats/118/19302.htm)

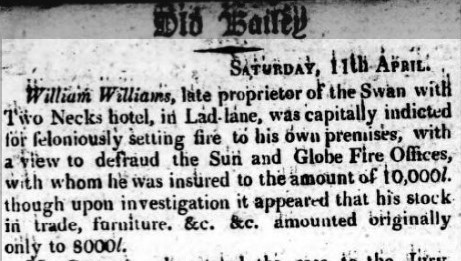

Following its success, many other companies set up similar businesses. ‘Initially, each company employed its own fire department to prevent and minimise the damage from conflagrations on properties insured by them.’ http://heritage.aviva.com/our-history/companies/h/hand-in-hand-fire-and-life-insurance-society/ . They issued firemarks (now very collectible) to denote which premises were insured. This system had an unfortunate flaw in that burning buildings were ignored if seen not to be ‘one of theirs’. The solution was eventually to establish a municipal authority to which the insurance companies contributed to establish a town fire brigade. This almost worked in that the fire fighters took no notice of whose firemarks were there but rather favoured those buildings that were insured against those that weren’t!

18th century doc image By Charles Simms [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; Cartoon by Hogarth recalling the position of prominence held by the Union Fire Office, 1762 from http://heritage.aviva.com/our-history/companies/h/hand-in-hand-fire-and-life-insurance-society/

It is interesting, but entirely coincidental, that one of the early companies, several mergers later, became what is now Aviva but which was for many years Norwich Union – another East Anglian connection?