The telegraphic call of CQ (pronounced sécu) had been used to alert all stations along a line. Rather as the beloved shipping forecast begins with ‘Attention all shipping’, CQ was the equivalent of ‘Hey listen up guys!’ There was no agreed emergency signal but in 1904 the Marconi Company instructed their operators that D (for distress) should be added, thus making CQD a telegraphic signal that help was required. At the same time the distress signal SOS was also being used interchangeably with CQD.

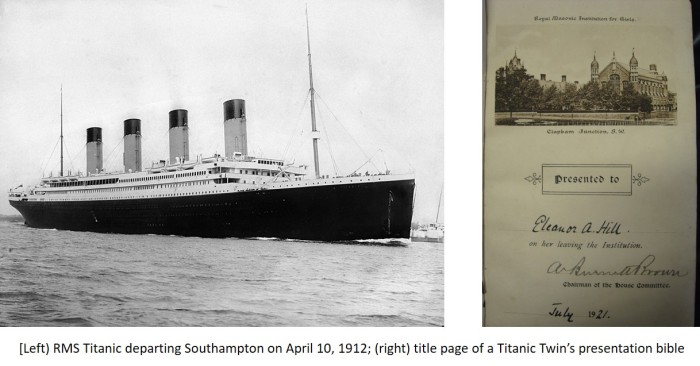

The two signals represented as Morse code might suggest that SOS was marginally quicker to send but in the hands of a skilled telegraphist the difference was minimal. One such skilled person was Jack Phillips, chief telegraphist on RMS Titanic. On the night of 15 April 1912, he initially sent CQD. Harold Bride, the junior radio operator, suggested using SOS. With a kind of gallows humour, and perhaps realising by this point that the unsinkable Titanic was going to do just that, he commented that it might be their only chance to use the ‘new’ signal. Phillips then began to alternate the two distress calls.

Phillips – and Bride who stayed in the radio room alongside him – was very much the hero of the hour, remaining at his post until Captain Smith issued the order to all crew to ‘save yourselves’ – an indication that all was lost. At the inquest, another radio operator who had picked up the signals commented that Phillips’ transmissions never wavered in their consistency or accuracy.

‘Jack’s last message was picked up by the Virginia of the Allen Line at 2.17am, and the Titanic foundered at 2.20am. ‘

http://www.godalmingmuseum.org.uk/index.php?page=jack-phillips-and-the-titanic

Because of telegraph messages, news of the ship’s fate reached newspapers in UK by the following day although there was clearly confusion in interpreting them.

But what has all this to so with the School? Well, this is the +RMIG bit of the heading. The Royal Masonic Institute for Girls had been established in 1788 to come to the aid of those in distress and the terrible loss of lives on the Titanic was certainly a time of great distress. Four girls who became pupils of the School did so because their fathers went down with the ship. Florence and Eleanor Hill, twin daughters of Henry Parkinson Hill (and known in School as the Titanic Twins) and Ethel and Brenda Parsons, daughters of Edward Parsons, all become pupils. Florence & Eleanor Hill and Ethel Parsons were at the School contemporaneously. Brenda Parsons, the youngest, two years old in 1912, would not have been old enough to be a pupil until 1918.

These fuzzy images are Florence Hill and Ethel Parsons as captured from a whole school portrait taken in 1913 (below).

Ethel and Brenda Parsons were the daughters of marine storekeeper Edward Parsons.

No doubt his family would have been extremely proud when he was appointed to the White Star line’s most luxurious and prestigious ship, little imagining the fate that awaited him. After all, the Titanic was unsinkable.

The Parsons family had been living in Liverpool and four of the children had been born there. They moved to Southampton sometime before 1910 and Brenda, the youngest child, was born there. As the wife of a member of ship’s crew, Mrs Parsons would always have been aware of the dangers of the sea but – the Titanic was unsinkable. What could possibly go wrong?

One of Edward’s grandchildren later commented that the family had a letter from the White Star line indicating that Eddie (as he was known) was last seen on the deck giving biscuits to children and comforting them. His body was never recovered or identified. His wages of £6 per month as Chief Storekeeper would have ceased with his death, leaving Mrs Parsons with five children to support on no income. She benefited from a Titanic relief fund but Edward’s Masonic connections meant that they too stepped in to offer support.

Ethel Parsons probably came to the School almost immediately after the disaster and left in 1920, accepted by Southampton Education Committee as a pupil teacher. Later she won a place at Hartley College, Southampton to read for an Arts degree but decided instead to train as an elementary teacher. She returned to the School in 1924 as a Lower School mistress, described as a temporary post, and she either left when she married in 1925 or slightly before. Thereafter, the School loses sight of her and it is left to public records to note that she probably died in 1994 in Surrey.

Her youngest sister, Brenda, little more than a baby when her father died, would not have become a pupil much before 1918 as eight was the usual admission age. It seems highly likely, however, that Mrs Parsons would have received financial aid before Brenda became a pupil as this was ‘part of the package’. She left school on 15th December 1927, undertook commercial training and by 1928 had a post in an insurance office. In 1929 she married George Holloway, a Congregationalist minister. In 1958, she married for a second time and became Mrs Tiller and she died on 22nd December 2008 in Eastbourne, not quite making it to her centenary but coming very close.

One of the Titanic Twins did make it to her centenary but let’s not jump ahead. They were the daughters of Henry Parkinson Hill and Florence Hill nee Baxter who married in 1903. Sadly by 1908 the marriage had failed and Henry had left the family home. The girls remembered little of their father as they were only 3 when he departed. Whether he went off to sea at that time or later is unclear but he was a 3rd Class Steward on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. His body too has never been recovered or identified. As he had been a Freemason, his daughters were eligible for support and they were elected to the School.

Eleanor’s time at the School is less well-recorded than her sister. She left school in 1921 and went to help her mother who ran an electric massage establishment. By 1923 she was nursing at the Treloar Cripple [sic] House in Alton but by 1927 was helping her aunt to run a boarding house so it seems her ‘career path’ was less clear cut than Florence’s. The school magazine records Eleanor’s death as being on 27th July 1976 ‘after a long illness’ and also notes that she was for a time assistant to the catering officer at the School.

Her sister Florence was clearly a bright cookie and was entered early for Local Examinations (equiv. of O and A levels then). Having passed them, according to her own recollections, the School didn’t know quite what to do with her as she was too young to leave. So she took them again the following year.

And the year after that!

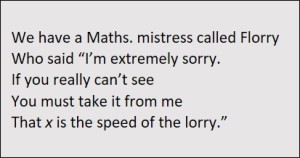

She declared that in her final years at the School she was bored out of her mind because there was nothing academically for her to work towards. She did not have the qualifications for university having no Latin, a requirement at the time. In 1922 she became a student teacher with Peterborough Education Committee and went to Peterborough Training College the following year. In 1926, she won a place at Bedford College for Women and emerged with a B Sc. upon which she returned to the School to teach mathematics. The following limerick was written by an unknown pupil about Florence.

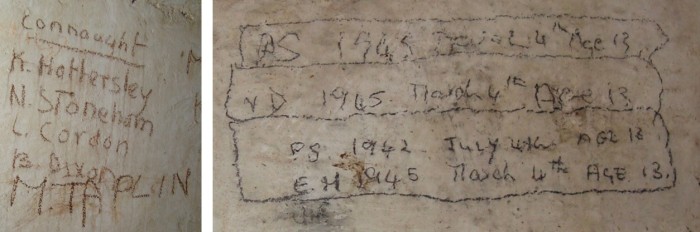

When the School moved to Rickmansworth in 1934, Florence moved with it and became Housemistress in one of the boarding houses (Connaught) before leaving in 1937 to marry the brother of one of her colleagues. In 1954, she came back to the School to teach until retirement in 1965. In 1994, she married for a second time, at the age of 89! She told friends that falling in love at 89 is just the same as falling in love at 29 – you feel all bubbly inside.

In 1999, she paid another visit to the School during which she entertained a group of Year 7 students with tales from the past of the School. They couldn’t quite comprehend a world where uniform was worn at all time except for pyjamas; where, having been in lessons all day, you spent the evening doing homework because there was little else to do. A world without television [today it would be smart phones]? Impossible!

After retirement, Florence lived in Lincoln and then Leicester. But a sedentary lifestyle it was not. Her nephew by marriage wrote of her:

You won’t be surprised to hear that at the age of 100 she organised her own birthday party, which was a truly joyful occasion, and one attended by numbers of her old pupils.

After the war, she had visited Germany a number of times and learned to speak German. She had been on one of these visits shortly before her death on 3rd November 2007 at the grand age of 102. Her death was sudden but peaceful in hospital where she was being treated for a broken collar bone, an injury that in a child is as nothing but in a 102 year old is a coup de grâce.

The death of Florence did not quite bring an end to the Titanic association. All girls were presented with a Bible on their departure from the school and in 2013, the School was contacted by an antiquarian book seller in Ireland to say he had found Eleanor’s Bible amongst a box of other books and would we like it returned? We would and it was! So a century after she was first in the School, something belonging to her was returned to it. 104 years after the Titanic disaster we can bring their stories to an end.