When the school began in 1788, girls had to be six before they could apply and no older than 10 when accepted. So the earliest pupils were primary school age – at least when they started.

The newspaper notices giving details of the first pupils in 1788.

They were at school until they were 15 which, at the time, was not the ‘norm’. If girls received any education at all – and many did not – it was generally until they were about 12. School log books are peppered with comments relating to girls leaving school: ‘Wanted at home’ was a common phrase. By the age of 11 or 12, girls were deemed perfectly capable of helping run the household, especially if Mother was still producing babies. By insisting that girls should be educated to the age of fifteen, the School was bucking the trend.

With just fifteen pupils to begin with, all pupils were taught together with the older ones helping the younger ones when required. As the school population grew, it became necessary to separate classes although the system of pupil teachers, used widely throughout the country, continued until well into the 20th century. Gradually, this segregation evolved into a system given the jazzy titles of 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th classes. Unlike today when, by and large, pupils move from one year group to the next by chronology, in the 19th century pupils graduated when their educational standard was deemed right. It was possible, if rare, for a pupil to remain in the lowest class throughout her time at the School and for her contemporaries to be much younger than she. For example, a pupil (who perhaps ought to remain anonymous!) was “in consideration of her age & height placed in the 3rd class” although the headmistress rather damningly said she “has scarcely met with such deficiency of mental power”. Hmm … (from RMIG Governess’ Report GBR 1991 RMIG 1/2/2/4/2 A11944)

Almost as bad was the girl who was

particularly wanting in ability, she is only in the 4th class and that more out of consideration for her age. She was only 11 when she entered the school, knowing nothing. (ibid)

En masse, the younger girls were described as ‘The Junior School’ or the juniors. Quite which pupils were classed as Juniors and which not is impossible to establish from a century away. The people of the time knew who they meant so did not explain and, by the time anyone had realised that there might be confusion, it was too late!

Above, a group photo, undated but probably at Clapham. Little girls with nice bows in their hair but there’s always one that looks as if butter wouldn’t melt …

By the time the School had reached its site in Clapham, the school roll had risen substantially and adjustments to accommodation were made. The houses next door had been purchased to give more room but this was only a temporary respite given the ever-increasing roll.

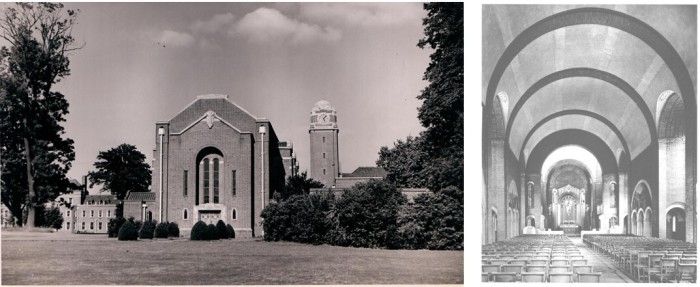

By 1918, bursting point had been reached and there was need for something more drastic. That something was the purchase of another site for the younger pupils and so, in 1918, we have the beginning of the Weybridge Years.

From 1918 to 1973, the younger pupils lived and were schooled in deepest, darkest Surrey and, inevitably, became known as the Weybridge girls. During WWII, when they were ‘evacuated’ back to the main school – by then in Hertfordshire – they were still known as Weybridge girls. New pupils who joined the school during these six or so years were often confused by this as they had never known the school anywhere else but in Ricky. For them, when the juniors returned to Weybridge post-war, this was a new place whereas for the old hands it was a coming home.

Above left: Miss Harrop who took the junior school to Weybridge, and kept its spirit alive during the war and (above right) Miss Vaughan, who took over post-war.

Above left: Miss Harrop who took the junior school to Weybridge, and kept its spirit alive during the war and (above right) Miss Vaughan, who took over post-war.

Abiding memories of girls were things like the panelled dining hall with its bowls of blue delphiniums [sadly no colour pictures exist]

And the gingko tree in the grounds, planted by Dr Roper-Spyers when he had founded the boys’ school originally there. Although the school buildings have long gone, giving way to a housing estate, the tree is still to be found.

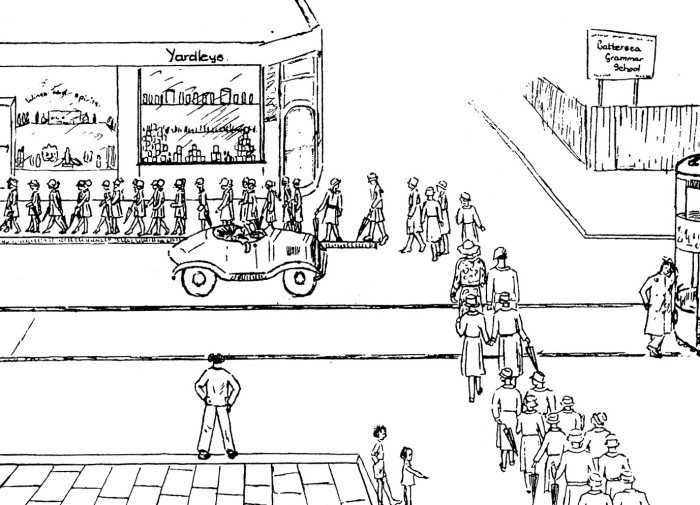

A flavour of Weybridge life is shown in the cartoons below, drawn by a former pupil.

The first captures the yawning middle-of-the-night fire drill, and the struggle into dressing gowns and coats and shoes, and resisting the temptation to snuggle back under the eiderdown.

The second relates to the cry that went up in the evenings “Long Hessen Elli Bedders”. Not as you might imagine some kind of esoteric schoolgirl language, the Weybridge version of pig Latin. In fact, it was a straightforward request for those with long hair (who needed to have it washed and dried before bedtime – long hairs) and those younger pupils whose bedtime was earlier than the others (early bedders) to come and be accounted for. Hence, long hessen elli bedders. Simple really.

The junior school was at Weybridge until 1973 when, with great reluctance but in the face of falling numbers, the decision was taken to close the site and transfer all pupils to Rickmansworth, permanently. To begin with, they were dispersed amongst the various boarding houses and attached to ‘house mothers’ who were, in reality, prefects. They had their lessons separately and, for many, any sense of continuity was focused on the figures of the Miss Gambles, known affectionately as Big Miss Gamble and Little Miss Gamble – although neither was of particular great stature.

The two ladies could be seen accompanying younger pupils after school too as they ventured around the grounds but of a ‘junior school’ there was little sign. Then, in 1980 David Curtis arrived as Headmaster and he reconvened the corporate body of the junior school by shuffling the boarding houses to provide a space for them. Not literally of course but certainly by name and purpose. Thus what was Ruspini house became Alexandra and Cumberland shuffled clockwise a couple of places; Atholl and Sussex became combined, reflecting the union between Ancient and Modern Freemasonry, led by the gentlemen of those names. What had been Cumberland became the Junior School and Ruspini, having shot across the Garth, became their boarding house. If you are confused by all of this, you are not alone. It took a good while to get used to the new positions of existing names. The Bursar’s department, working on the basis that more changes might well happen in the future (they did, but not for a good while) referred to the houses as K1-K8 on the basis that the order would remain even if the names changed. No-one knows why they chose K.

The Js (as they were nicknamed) settled in their new homes and the Seniors eventually stopped grumbling about the changes. By the time of the Bicentenary (1988), few, if any, of the pupils could remember it being any different. Of course, former pupils remembered well their houses and even now, when Old Girls visit and ask to be shown their house, they are startled to be taken by a current pupil in a completely different direction than they had expected!

At the back of the House/Junior School, an adventure playground was installed in the 90s, a recognition that younger pupils needed something to get rid of excess energy during breaktimes! The Junior School remained in the Garth for the rest of the century although an expanding school roll again put pressure on the space. This was further exacerbated in 1994 when the starting age for pupils became rising five. The Junior School was renamed the Prep Department so that the very youngest pupils could be classed as the Pre-Prep. In 2009, another new venture introduced even younger pupils as a Pre-School opened with pupils aged 2+ (and some of them of a different gender). In order to avoid confusion with nomenclature (!!), Ruspini House became the home of the teeny-tinies which left the Junior Boarding House without a name. The obvious choice was Weybridge.

In the meantime, other changes had been made (no, don’t go there) which left a large building within the grounds unoccupied. It was refurbed, had an assembly hall added and in 2011 the Prep and Pre-Prep Departments moved lock, stock and barrel and became Cadogan House.

The creation of a combined Prep and Pre-Prep meant eliminating the final traces of the old operating theatre which had been a part of the building when it was the Sanatorium.

It also meant leaving behind the adventure playground but, fear not! Another one was built.

This historical overview of the younger pupils one hundred years after the founding of the school at Weybridge is brief. Much more can be seen on the School website rmsforgirls.org.uk but, as punctuation perhaps, here’s a fashion parade of little misses over the years.