In today’s boarding school world, where there is frequent leave of absence for boarders, the notion of a girl going to a boarding school and not going home again for five years must seem very strange. However, when RMIG (or the Royal Cumberland Freemasons’ School as it was then) first started it was thought important that a girl’s time at school was not interfered with at all. Parents were actively discouraged from contacting their daughters. In fact ‘visiting time’ was limited to Thursday afternoons only and, even then, by appointment. As the school was in London, anyone living outside the capital would have found it very difficult indeed to visit. If parents insisted on contacting their daughters, they might be told to take them away again and be given a bill for their education to boot. Added to this, the phrase used to note the outcome of a girl’s education was the rather chilling one of ‘How disposed of’ – which to modern ears sounds like the prelude to a murder mystery.

Once a girl left the School, she could be returned to her parents, or surviving parent, or to her Friends (i.e. whoever was acting as a guardian) or be apprenticed in some way. In the early days, this was almost invariably into domestic service rather than a trade but later it often became training for nursing or teaching, some of which training may actually have taken place at the School before further training elsewhere. Some girls did go home to parents and the parents placed them in work/training but it is remarkable how many girls left home to attend the School and never really went home again. They probably visited family but, having left the family home as children, they often went into the world of employment away from home and made their new post-school lives from there.

One such is Gwendoline Hammersley Warrillow who became eligible for a place in the School upon the death of her father (see Cheaper by the Dozen) and left the School in May 1894. The Head Governess had this to say of her:

[she] “has been a good girl and has done well generally but hardly as well as she might; consequently she has not succeeded in gaining any prize; she passed College of Preceptors exam P Class III Div II”. Library & Museum of Freemasonry GBR 1991 RMIG 1/2/2/4/1-4 A11943 – A11946

Hmm, hardly a ringing endorsement but actually better than some. Sarah Louisa Davies, the Head Governess, did not often mince her words!

Gwendoline’s story began on 3 May 1878 and she was baptised at St John’s, Hanley 27 days later.

Image of St Johns is drawing by Neville Malkin and reproduced from an out of print book. http://www.thepotteries.org/tour/hanley/065.jpg

At this time, the Warrillows were living at Grove Lodge, Snow Hill, so named because it was originally a deep cutting with unpaved roads frequently blocked by snow in winter. Presumably the lodge was that for Grove House which was described thus:

“Grove House, altered and enlarged by Charles Meigh c. 1840 and at that time containing a fine collection of pictures, stood near the junction of Snow Hill and Bedford Road.” http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/staffs/vol8/pp142-154

“The main road was formerly known as Snow Hill only between the present Cutts St. and Wood Terrace and as Broad St. from Wood Terrace to Victoria Sq.; it then continued as High St. up to the junction with Marsh St.: Hargreaves, Map of Staffs. Potteries.” http://www.thepotteries.org/location/districts/howard_place.htm

A much magnified image from Thomas Hargreaves’ map of 1832 may show the lodge, although this is by no means certain.

http://www.thepotteries.org/location/districts/howard_place.htm

A much later resident of Snow Hill – long after the Warrillows had departed – was Clarice Cliff. The image of houses in Snow Hill today perhaps reflects the quality of the housing stock once although most of these are now sub-divided (and sub-sub-divided) into flats.

Having left school, we catch up with Gwendoline in the 1901 census – in Tadcaster, Yorkshire. This is so far removed from her previous sphere as to suggest that the School played a part in placing her there as governess to the Pickering family. We don’t know that for certain of course but, however she arrived at this situation, it certainly changed her life for ever. Four years later she married the son of the family, the marriage being announced in the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer of 05 September 1905.

The banns were read in St Mary’s, Garforth and in Stone, Staffordshire – a nod to her Staffordshire roots. Just to clarify the situation, it should be pointed out that John Herbert Pickering was some six years Gwendoline’s senior so most decidedly not one of her charges!

Six years later, the 1911 census places the couple, now with their two children, in Station Rd, Garforth. John Herbert Pickering was continuing the family business as a cattle dealer and butcher. Station Rd today has modern houses which appear to date from much later than 1911 so it seems likely that the area was redeveloped after the Pickerings had left it for pastures new. The next recorded address for the family is Coney Springs, Robin Hood Road, Ravenscar where, sadly, their daughter’s death was announced in 1936.

Captured from Google Earth

At what point the Pickerings moved from Garforth to Ravenscar is not known and they could have been elsewhere in between. It is also worth noting that death notices for both Gwendoline and John give them as ‘of Garforth and Ravenscar’, rather as if they possibly lived in both places.

Ravenscar is in itself an interesting place.

“Standing on the fringes of the rugged North Yorkshire Moors and perched on the top of 600 foot high cliffs overlooking the North Sea sits the village of Ravenscar, the ‘town that never was’, or the Victorian dream that failed.” https://antonyjwaller.wordpress.com/travel-articles/yorkshire-and-northern-england/peak-the-yorkshire-town-that-never-was/

In the heyday of Victorian railways, the idea of developing a seaside town, purpose-built to be served by a new railway line, where not only holiday makers would flock but so too would hordes of people clamouring to buy one of the 1500 plots made available and having a house built. Unfortunately, it was one of those ideas that looks good on the drawing board or on a flat map but which never quite takes in the reality of the geography. A place with stunning sea views it may be but there is the small matter of a 600 foot cliff separating this ideal location from the shoreline – which was not even a sandy beach anyway.

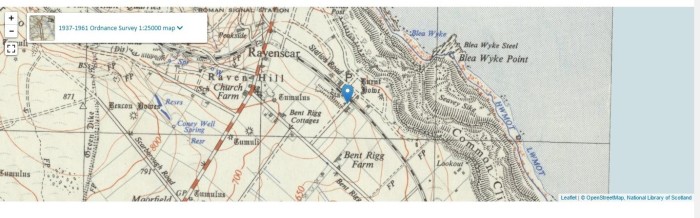

The map above shows clearly the steepness of the cliffs. This is from FindMyPast showing where the Pickerings lived in 1939 (although mistakenly interpreted as Casey Springs).

“Access by train proved to be difficult with trains often struggling to overcome the steep gradient of the newly built line. With Ravenscar’s exposed cliff top location often at the mercy of the wind and rain, a rocky shoreline hundreds of feet below with difficult access and no proper sandy beach this particular Victorian ‘new seaside town’ failed.” https://antonyjwaller.wordpress.com/travel-articles/yorkshire-and-northern-england/peak-the-yorkshire-town-that-never-was/

Instead of Ravenscar becoming a thriving seaside destination to rival Whitby or Scarborough (between which two places it lies), it remains today something of a ghost town with roads laid out and a station platform built to offload the hordes of trippers who never arrived and a few scattered houses. Two of these, Coney Springs and Broom Rise, were occupied in turn by the Pickerings. In the 1950s, Broom Rise was their given address. Ravenscar still has stunning sea views as shown in this picture from Antony Waller’s blog.

The station closed in 1965 and the tracks have since been lifted although the ‘up’ platform is still there.

The death notices referred to above show that, at the end of their lives, both Gwendoline and John died in Leeds. The address, Weetwood Lane, was the home of their son. They died just a year apart with John being described as a dearly loved husband in the newspaper’s announcement. Both of them left their estates to their remaining child, Thomas Warrillow Pickering, who was continuing the family business of being a butcher. Perhaps following the death of his father or perhaps because his mother was aging and he was concerned about her living in a relatively remote place where neighbours were probably at least a field away, Thomas may have insisted that his mother come to Leeds. We are not party to that discussion. The fact remains, however, that the following year when Gwendoline died in St James’ Hospital (‘Jimmy’s’), her address was given as Weetwood Lane. So, even in her death, Gwendoline Hammersley Pickering, nee Warrillow had ‘left home’. Her burial place is not given in the public records but as her daughter and her husband were both buried in Ravenscar parish church, it seem likely that Gwendoline was too.

http://s0.geograph.org.uk/geophotos/01/54/71/1547151_a3f53863.jpg

My thanks in this posting and the last to SuBar who, to mimic the old Heineken ad, reaches parts of the research others can’t reach!