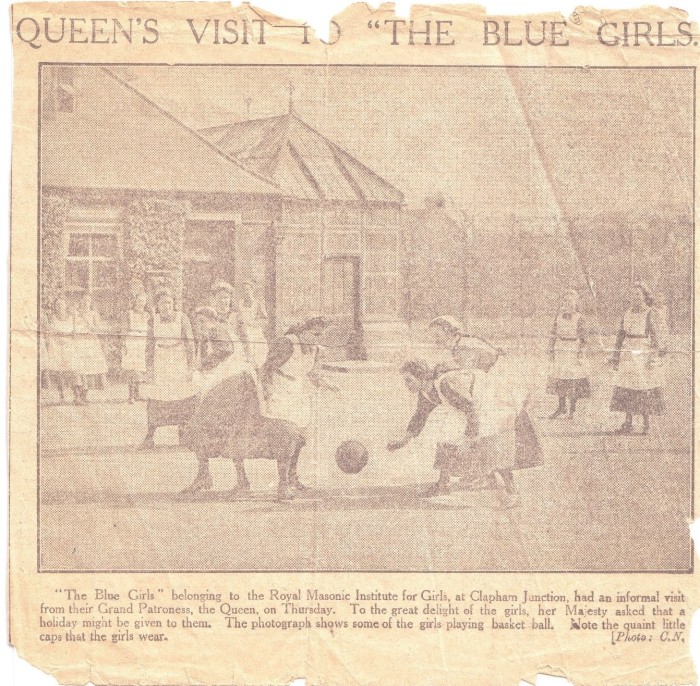

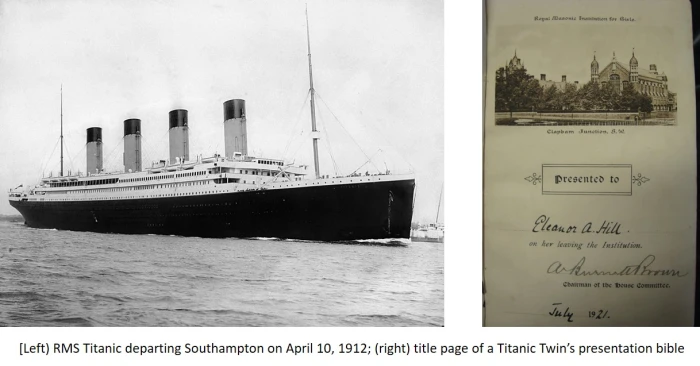

Last time, we considered the School at Clapham in the nineteenth century. All of the pupils who came and went over that period have the School in common although they are, of course, individuals in their own right. They all have their own stories to tell. Tracing the individuals to find the stories is relatively straightforward if they remain within the UK. It is when they slide out of reach by ‘Going Abroad’ that it starts to be trickier. And when most of the life being researched is actually overseas, it can be a challenge. One such is Bessie Phear Woodford Locke, who appeared on only two UK census returns (30 years apart), and her story may never have been uncovered were it not for a brief comment in Massonica [sic] in June 1913.

‘Lady Hamilton is well-known to many of us as Bessie Locke, silver medallist of her year.’

But we are jumping to the end of her story here so let us go back to the beginning.

Bessie was the daughter of Henry Hover Locke and Louisa Jane Locke, nee Woodford, and she was born on the 14th February in Dumdum, near Calcutta (today Kolkata) in 1876. She was baptised on 25th March 1876 at St Stephen’s Church, Calcutta.

Her father was the Principal of the Government School of Art in Calcutta, an architect by training. From Wikipedia, we learn that this school began in 1854 at Garanhata but within months had moved to Mutty Lall Seal in Colootola.

‘In 1864, it was taken over by the government and on June 29, 1864 Henry Hover Locke joined as its principal’.

Dumdum, where Bessie was born, is a name derived from the Persian word damdama, which refers to a raised mound or a battery. During the 19th century there was a British Royal Artillery armoury there. Here in the early 1890s, Captain Neville Bertie-Clay developed a specific type of bullet which came to be known as a dumdum bullet. More properly known as an expanding bullet, its design is specifically intended to maximise damage and it has been long prohibited for use in war.

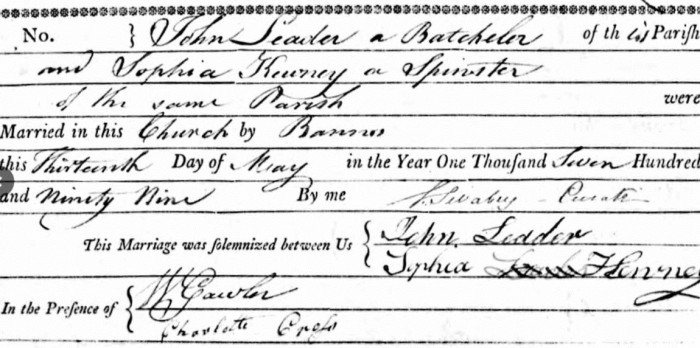

Bessie and her sister were both born in India but so also was their mother Louisa Jane Woodford so they were Empire families across at least two generations. Bessie’s grandfather was Charles Thomas Osmond Woodford, a surgeon, serving in India. He was born in London in 1821 but in 1845 he married Jane Cunnew in India. She was also from London (b. 1819). They were married in Dacca (now Dhaka) in 1845. Charles Woodford

‘Joined the Uncovenanted Medical Service, Bengal, in 1848; he was Surgeon to the Calcutta Police and ex-officio Professor of Medical Jurisprudence in the University of Calcutta.’ https://livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk/

He died ‘of general debility’ in 1881 in Coonoor, Madras but lived long enough to see his daughter Louisa married in 1873 at St Paul’s Cathedral Calcutta, and the birth of his granddaughters.

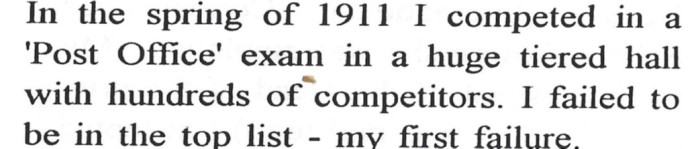

Bessie would have been five when her grandfather died but it is possible that she hardly knew him as he died in Madras (now Chennai) about a thousand miles from where Bessie and her family resided. Sadly for her, however, just four years later her father died too, on Christmas Day 1885, the cause of death given as heart disease and heat apoplexy. In his will, he named his wife, Louisa Jane, as his sole beneficiary and appointed her as guardian of their infant children. Because of her father’s death, Bessie came to the School (Petition No 1456) possibly in 1886. What else she did or did not do during her time at school, we know that in 1890 she was entered for the Senior Cambridge Local Examinations which she unfortunately failed. Sarah Louisa Davis, Head Governess, never one for pulling punches if she was annoyed with girls, was clearly sympathetic in this case.

‘The one failure is Bessie Locke, a most persevering good girl, quite worthy to be entered but of an anxious disposition; she may have failed to grasp the meaning of some things in the exam particularly arithmetic.’

She tried for a second time in 1891 but the arithmetic let her down again.

Nevertheless, the Head Governess wrote of her that she ‘has always been a specially good girl and by attention and perseverance has attained a good position in her classes’. In 1892, Bessie was awarded the silver medal.

In 1892, it was written [she] ‘passed Junior Cambridge Class II Hons. And has prizes for Religious Knowledge & French’. On this basis, she was recommended to take the vacancy as pupil teacher to teach ‘little girls’. She was given a year’s trial but, at the end of this period, Miss Davis ‘felt that there was little point in continuing as she would not attain to any higher level of teaching … she will be better placed in a private school in England or abroad where she could improve her languages & music and therefore able to obtain a post as a governess, which would suit her better than teaching in a large school. Miss Davis cannot speak too highly of her personally and she recommends that she receives the ex-pupil’s grant.’ And in pencil afterwards is written £40.

Where Bessie went to after this is currently unknown. She is not located on the 1901 census so it seems likely she returned to India where, in 1909 in Rawalpindi, she married Henry Hamilton.

Henry was considerably older than Bessie, being born in 1851 at Coolaghey House, Raphoe, Co. Donegal. He had been educated at the Royal School in Raphoe before going to Queen’s, Belfast. He qualified first as a lawyer before going on to medical training, where he graduated in 1875 as M.Ch. The following year he joined the Indian Medical Service as a surgeon and served with the 23rd Bengal Native Infantry. It is possible that he had known Bessie all her life as he first went to India in the year she was born.

In Crone’s Dictionary of Irish Biography it records: “HAMILTON, Sir Henry, Surgeon General; b. Coolaghey, Donegal, 1851; ed. Raphoe and Q.C.B; B.A. 1872; M.D., 1875; entered I.M.S., 1876; took part in march to Kandahar, 1878; senior M.O. Chitral Expedition, and principal M.O. China Expedition, 1900-1; C.B., 1904; K.C.B.; d. Mentone 1932’

He was several times mentioned in despatches and received special promotion to Brigade Surgeon Lieutenant-Colonel. Further promotion followed, being advanced to Colonel in October 1902 and in March 1907 –

‘To be Surgeon-General Colonel Henry Hamilton, M.D., C.B., V.H.S. Dated 25th March, 1907’ – The London Gazette.

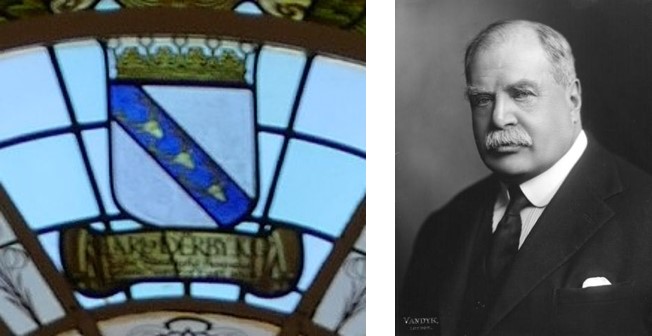

He retired in 1911 and in 1913 was invested with the KCB (Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath) and his arms would have been displayed in the Henry VII Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey.

In 1921, Bessie and Henry are listed in Romsey, Hampshire. Whether this was their home or they were visitors is unclear. Henry died on 21st Jan 1932 in Menton-Garavan, on the French Riviera. Bessie, despite being 25 years younger than her husband, survived him by only a year. She too died in Menton-Garavan so this would appear to have been their home.

Like so many of the pupils, Bessie arrived at the School as a fatherless daughter. She did her very best with her lessons, then returned to her roots in India before marrying, ultimately becoming Lady Hamilton. Bessie’s life from the Raj to the Riviera with a stop-off point in Clapham!