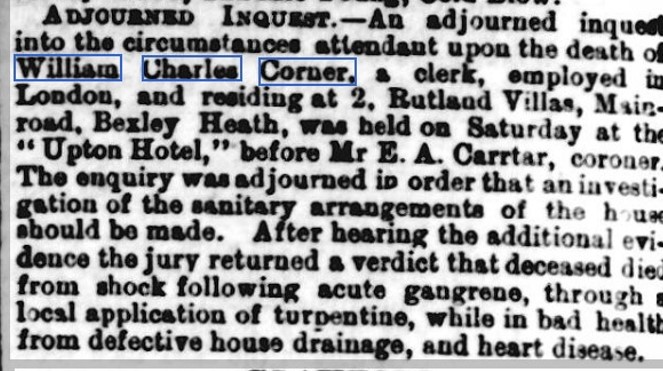

This particular corner is not a place but an individual – Ellen Ethel Corner, daughter of William Charles and Louisa Ellen Corner. Her father, a member of the South Norwood Lodge until 1887, was given as a chartered accountant but later as a clerk which implies a diminution in status. He died in 1890, his death being attributed to a combination of bad drainage in the house and heart disease. The Maidstone Journal and Kentish Advertiser on 05 August 1890 reports the inquest and apparent cause of death.

His personal estate value was given as approx. £124 so, even if he had survived, it is quite possible that Ethel (as she was known at school) would have been eligible for a place because of her father’s indigence.

Ethel was 5 when her father died so would have been too young for the School. Sadly however, in 1893, her mother also died, leaving all three children orphaned. Ethel, now aged 8, was the correct age for admission and a petition was drawn up for her. She became a pupil subsequently and is found in the census return at the School in 1901. Her brother became a pupil at the Boys’ but the remaining child was not accepted although she may have been found a place elsewhere.

In 1901, Ethel was awarded the Supreme Council Prize for Good Conduct, an indication of both ability and behaviour. It was an accolade not given lightly. The following year, she left school and went to Brighton College for two years to train as a teacher. In 1905, she secured a teaching post at Upland Council School, Bexley Heath.

In the 1911 census, Ethel confirms her status as a certified teacher working for Kent County Council. She was a boarder at The Broadway, an address less than a mile from the former family home.

A year later, she gave her address as Rutland [Villas], Crook Log, Bexley Heath so it would appear that this was still in the family’s possession as it seems likely to be the same address given in her father’s records. In 1912, Ethel attended Ex-pupils’ day.

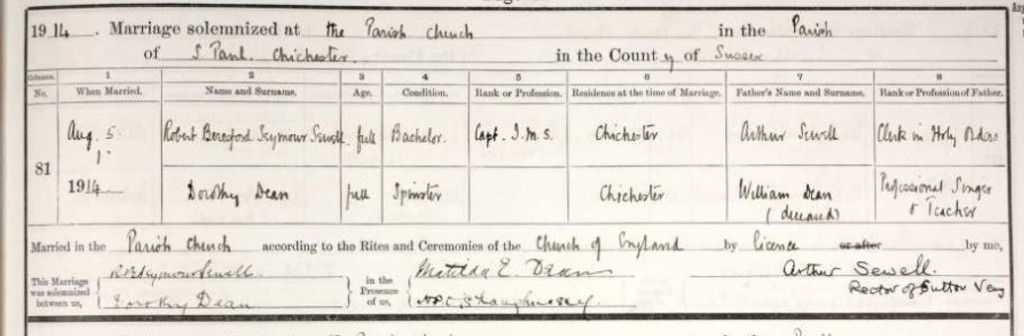

She also attended Ex-pupils’ day in 1914, the year she married Henry Eric Kyrle Fry. He was the son of Henry Lawrence Fry, the vicar of Christ Church, Bexley Heath. This must have been the family church as Ethel’s sister was baptised in the same place by the same person. Ethel and her husband may well have known each other growing up.

It is interesting that, although they married in her father-in-law’s church, the person conducting the ceremony was the vicar in Fareham for whom Henry Fry was the curate. The marriage took place 13 days after war was declared. Perhaps he was expecting to be posted overseas as it is known that Henry served as Chaplain to the Forces during WW1. In 1918 he was serving in Italy.

In 1921, Ethel and her daughter were visiting friends (the Passmores) in Bexley at the time of the census. Henry is listed at the vicarage of St Mary to which he had been appointed in 1915.

In 1923, Revd Fry was appointed as vicar to St Mark’s in Wellington, New Zealand and the family arrived there on 28 May 1923 on the Ionic. They obviously hit the ground running as on 3rd June, he was instituted as vicar and The Evening Post of 7 June 1923 indicated that

A SOCIAL to welcome the Rev. H. E. K. Fry and Mrs. Fry will be held in the Schoolroom, Dufferin street THIS (THURSDAY) EVENING, at 8 o”clock.

All Parishioners cordially invited.

Then in September of that year a bazaar was opened ‘by Her Excellency Viscountess Jellicoe’ (ibid.) during which Honor Fry presented Lady Jellicoe with a bouquet. Honor was an experienced presenter by this stage as the Hampshire Telegraph of 15 September 1922 indicates that ‘Little Miss Honor Fry’ presented a basket of fruit to the wife of the speaker at a Portchester garden party. Honor would have been 4 years old then so at five this sort of thing was old hat. Easy-peasy, lemon squeezy!

Mrs Fry’s later obituary in the Evening Post gave the information that

‘Soon after, arriving in New Zealand she was approached by Lady Jellicoe to take an interest in supporting a Girl Guide movement in New Zealand.’

It is not known if Ethel had been involved in guiding before her departure for New Zealand but her husband had been involved in the scouting movement so it is possible and that this is why Lady Jellicoe had approached her. The newspaper went on to say

‘Mrs. Fry addressed a very large public meeting in the Wellington Town Hall at the initiation of the movement, and became the first Girl Guide Commissioner for Wellington South’ and that she was ‘a most able and accomplished speaker’.

Learning to speak in public was a skill available to the more accomplished pupils at RMSG so, although there is no certain evidence for this, it seems likely that she had elocution lessons whilst at school. It is notable even today that senior girls leave the school with confidence about speaking in public.

But guiding is not all Ethel was involved in. Her obituary declared that

she was an outstanding success on every side of church work. She was Dominion president of the Anglican Girls’ Bible Class Union, as well as for four years Wellington Diocesan president. She was a gifted Bible class leader, and conducted large Bible classes for girls, both at St. Mark’s, Wellington, and at St. James’s, Lower Hutt. She was a prominent member of the Mothers’ Union Council, and for ten years was president of the Lower Hutt branch.

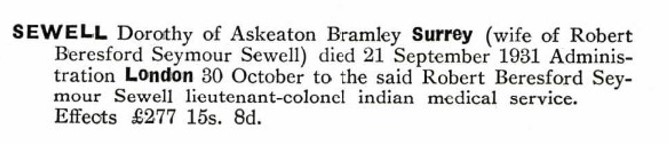

The electoral roll for 1928 gives Ethel as residing at The Vicarage, Dufferin St, Wellington and the membership list for the Old Girls’ Assoc confirms she remained in touch. By 1939, her address was listed as The Vicarage, Lower Hutt, New Zealand. Henry Fry had been appointed as vicar of St. James’ Church, Lower Hutt in 1933.

In 1942, the engagement of their daughter Honor Fry was announced followed by the marriage a year later conducted be her father.

‘FRY – On October 1, 1945, at Wellington, Ellen Ethel, beloved wife of Canon Fry and mother of Honor and John. Funeral Service at All Saints Church, Otaki, on Thursday, October 4, 1945’

She is buried in Otaki cemetery.

Her death and burial is recorded a long way from where she was born but one has the impression that, wherever she had lived, she would have been noted. Definitely a credit to the School that nurtured her after an unfortunate start being orphaned aged 8: a Corner of Kent occupying a corner of Otaki in perpetuity.