Golden Square Flowers

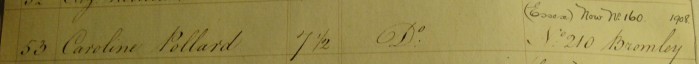

Caroline Pollard, the 53rd child to enter the Freemasons’ School, was the daughter of George and Susannah. She was born in Bromley St Leonards in 1788 and baptised at St Mary’s on 11th July 1790. She may well have been one of eight girls born to Mr & Mrs Pollard but it is difficult to be certain as the baptismal indices do not supply dates or places. There were eight girls born to a George and Susannah Pollard (and two sons) but the only ones we can be certain about are Caroline, Charlotte, Lucy and Sarah as they all appear together in census returns recorded as sisters.

The village was named after a priory of the same name, a convent founded in the early days of William the Conqueror’s reign, and immortalised by Geoffrey Chaucer in the prologue to The Prioress’s Tale:

(Image of Prioress from http://www.luminarium.org

Chaucer’s apparently complimentary descriptions, far from praising Madame Eglantine’s ability to speak French, is in fact a barbed reference to her speaking with a low class accent and probably an imperfect understanding of the language, learned at the nunnery rather than in France. Chaucer is drawing attention to the fact that an Englishwoman is rather pretentiously speaking French as she thinks it befits her self-perceived status whereas she is speaking it with an ‘East End’ accent, so every word she utters gives her away!

The village retained the name after the Dissolution. There is now no trace of the convent except the chapel of St Mary and part of a wall in the churchyard. What ruins of the convent that might still have been left were demolished to make way for the Blackwall tunnel, opened in 1897. (information from http://www.aim25.ac.uk & Wikipedia )

(Image of gateway from http://hidden-london.com/gazetteer/bromley-by-bow/ and of St Mary’s church from http://www.mernick.org.uk/thhol/p_stmbro.html )

Caroline was admitted to the School at the age of seven and a half in 1796. Unlike many pupils, she was at the school for just over four years, leaving in October 1800. At that point she ‘was returned to her parents’ (rather than apprenticed anywhere) so we do not know why she left at the age of 11 rather than the normal 15. From there until the 1851 census, there is a kind of ‘radio silence’ and we do not know what she did. In 1851, she lived at 8 Warwick St, Golden Square with three sisters.

John Strype wrote of Warwick St that it was ‘a Place not over well built or inhabited’ A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, 1720, vol. 11, bk. VI, p. 84, cited by www.british-history.ac.uk). ‘Golden Square Area: Warwick Street‘ (in Survey of London: Volumes 31 and 32, St James Westminster, Part 2, ed. F H W Sheppard, London, 1963) goes on to say that ‘Nos. 7 and 8 are only the back of Holland and Sherry’s building in Golden Square’ http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols31-2/pt2/pp167-173. Although Holland and Sherry began trading in 1836 it was not until 1886 (i.e. after Caroline and her sisters were at No 8) that the business moved to Golden Square. (information from http://www.hollandandsherry.com/apparel/story.aspx)

Nos 5-8 Warwick St are currently Hammersley House which, although a listed building, seems to have a different style to its two neighbours. It seems likely that the original building matched its neighbours.

Further along the street is the Catholic church of St Gregory ‘pillaged during the so-called Gordon Riots of 1780 … the last time that Catholic property in London was destroyed by rioters.’ http://www.ordinariate.org.uk/groups/london-central.php

In the 1861 census, all four sisters continue to reside at No 8 but by now are described as lodging house keepers. Their sole lodger (at the time) was a man described in the census return as a ‘popish priest’. It is unclear who has thus described him – the enumerator or the sisters – and whether there was therefore any religious disapproval intended in the use of the word popish.

In 1851, all four sixty-somethings sisters – Charlotte, Lucy, Sarah & Caroline – were engaged in flower making. https://19thcenturyhistorian.wordpress.com/2013/07/22/a-is-for-artificial-flower-makers/ is very informative of this industry and the role of women within it, noting that most census returns recorded some reference to it ‘despite the fact that making artificial flowers was generally a poorly paid and seasonal occupation.’ It should be noted, however, that Caroline and her sisters employed a household servant in 1851 which either means that they were earning enough from the business to employ one or that they had other money and the flower-making was an occupation rather than a necessity. As they were at the same address ten years later perhaps they owned it although we cannot know for certain. By 1871, the same address is occupied by the Pontet family.

Artificial flowers were big business. They were used to decorate clothing and all but the poorest could afford a few pennies to buy some.

‘astonishingly detailed, hand-assembled flowers were used to decorate dresses, bonnets and hats’ https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/lost-art-flower-making

It should be pointed out here that there were a variety of levels within the trade from the lowest paid ‘more a case of artificial flower mounting – also known as ‘sticking and papering’, or ‘sticking and wiring’, than artificial flower making’ (https://19thcenturyhistorian.wordpress.com) through to people like Emilia ‘Emma’ Fürstenhoff ‘internationally known for her manufacturing and arrangements of artificial flowers of wax, which were a novelty in contemporary Europe.’ (Wikipedia) The ‘sticking & papering’ was paid by the gross and ‘varied from 1¾d to 2½d; the gross took about an hour [to complete].’ (Clementine Black, Married Women’s Work, (London, Virago, 1983), p 31 cited by https://19thcenturyhistorian.wordpress.com)

Flowers were created in a multi-layer process with the heavier manual work (the cutting of the fabric into petal shapes with tools struck by mallets) being done by men. Then the fabric was dyed and left to dry before the women began a process to ‘vein’ the petals to give texture.

‘ …real flowers have concave petals, not flat ones, so the flower-makers would have a tool with a round metal ball on the end, and heat it over a spirit lamp. Then they would press the petal to shape it around the ball.’ (https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/lost-art-flower-making)

(Image above from https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/lost-art-flower-making)

Once the petals were made, they were then assembled into flower shapes with wire and the flowers into sprays, the wire being covered with silk or paper.

‘Artificial florists were everywhere – it was a job that a woman could do in her own home, with little experience, and which could supplement the household income, and if not actually raise the family out of poverty maybe at least ensure that the roof stayed over their heads for another week.’ https://19thcenturyhistorian.wordpress.com

It could also be done by the disabled, for example, who may have struggled to find other employment.

‘… the Flower Girl’s Christian Mission, where blind and disabled girls from around the City worked to make flowers that were sold for charity. They produced some of the first poppies for the Royal British Legion.’

Information from http://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/discover/lost-art-flower-making

The 1891 census recorded 4011 flower makers but as the nineteenth century progressed, the trade became more devalued so that Black’s survey of 1905-8 cited the pay for creating a dozen bunches of eighteen leaves bound together with fine wire being 2d.

Quite what end of the scale the Pollard sisters were at is impossible to say. Nor do we know for how long they were engaged in the trade. They were recorded as artificial flower makers in 1851 but not by 1861. They may have been skilled or they may have done this briefly as a means of occupation – a hobby that brought a small income. Unfortunately, because of the big gaps in her story we do not know how Caroline Pollard spent the greater part of her life. Neither she, nor any of her sisters who lived in Warwick Street, married but presumably were close as they shared a home and two different occupations during their lifetimes. Caroline died in 1864 and was buried at All Souls, Kensal Green on 30th July, her age given as 65 (it was actually 76!) but the address is correct so we assume this to be her. I wonder if there were flowers on her grave?