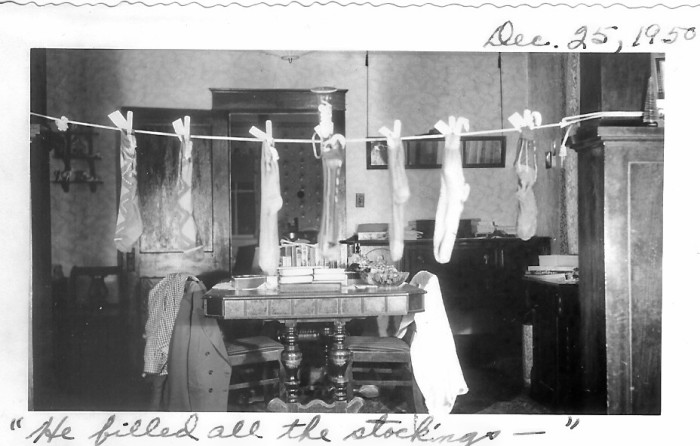

“The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there.”

– A Visit from Saint Nicholas, Clement Clarke Moore, 1823

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-legend-of-the-christmas-stocking-160854441/

The Christmas stocking, hanging from the mantelpiece, bed post, or anywhere else (like the washing line above), is a Western tradition. The aim is to leave an empty stocking which, by magic, will be filled by the next morning with small toys, or tangerines, or sweets or chocolate coins in bright foil or anything else that can pass muster as a stocking filler. Apart from a foot that is.

It is tied in with the folklore surrounding the character of Santa Claus or St Nicholas and, although the stories all vary slightly, the concept of St Nick as a gift-giver is common to all of them. Although originally the stockings were likely to be those normally worn, some were created especially for Christmas and it didn’t take long for the commercial arm to work out that the idea could boost Christmas sales no end. Today Christmas in the Western world is a Commerce Fest but the image below shows that this is not an entirely modern phenomena as it dates from a century ago.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-legend-of-the-christmas-stocking-160854441/

Stocking fillers were intended to be cheap and cheerful gifts. There could be all sorts – but you rather hoped it wouldn’t be a piece of coal marking your naughtiness – and that’s what this School Christmassy stocking contains.

The fillers, not the coal.

This is a small collection, definitely not commercial, of unconnected stories related to the School’s history.

The bulging stocking hangs tantalisingly. Let’s see what’s there.

If you have been enjoying Blue Planet II with the inimitable Sir David Attenborough, you might be surprised to know that, but for a quirk of fate, it might have been the voice of Jack Lester. Jack – or more properly John Withers Lester – had been the curator of Reptiles & Insects at London Zoo. At that time, the usual way zoos acquired their animals was from expeditions and Lester had organised one such to Sierra Leone. David Attenborough had previously produced and presented a nature programme and during this he formed a friendship with Jack. He was then invited to go on the expedition, with a film crew, and, as Attenborough was very keen to film animals in the wild, he jumped at the chance. It was this expedition which formed the basis of the series Zoo Quest. The original idea was that Attenborough would produce the programme but that Lester would be the presenter. Unfortunately, Lester contracted a tropical disease from his trip to Africa and presented only one instalment before having to be taken to hospital. Sadly, after several recurrences, this was what caused his premature death at the age of 47 in 1956. Because the series was already scheduled, Attenborough had to take over the presentation. And the rest, as they say, is history.

And the connection to RMSG? Well, Jack’s daughter subsequently became a pupil between 1957 and 1964.

On the subject of zoo expeditions, someone who wrote entertainingly about them is Gerald Durrell. One of his expeditions was to what was then British Guiana, mentioned in the last post Bring Me Sunshine. In 1950, Durrell discovered the name Adventure on a map of Guiana and thought it sounded perfect as a starting point.

“ ‘Three singles to Adventure please,’ I said, trying to look as nonchalant as possible.

‘Yes, sir,’ said the clerk. ‘First or second class?’ “

(from his book Three Singles to Adventure written with the characteristically wonderful Durrell imagery and humour.)

Given the similarity to the Lester expedition, one is not surprised to find a certain person commenting that Durrell was –

‘A renegade who was right… He was truly a man before his time’

Sir David Attenborough

Halfway down the stocking leg now

Continuing the animal theme – and equally as contrived – we have Emilie Hilda Nichols who was a pupil at the School in the C19th.

This small item appeared in Horse and Hound: A Journal of Sport and Agriculture, on September 17, 1892. Applicants for the School had their names and details submitted by Petitioners and were then put forward to a ballot. This was circulated, voted upon and the totals added up. Those girls who received the most support were granted a place at the School (always over-subscribed) and those unsuccessful accrued their vote totals for the next ballot six months later. This could happen several times, unless the girl in question became too old to be accepted as a pupil (usually 10 years of age). It seems rather more unusual for something to appear separately, and additionally, in a publication concerning a particular child – a sort of belt and braces approach. It seems likely that ‘Retniop’ knew William Nichols; Retniop was writing for Horse & Hound and Nicholls was the editor of Stock Keeper and Fancier’s Chronicle, described as ‘A Journal for Breeders and Exhibitors of Dogs, Poultry, Pigeons, Cats, &c’ – their subject matters were similar.

Image of cover from http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery

By the late 19th century, there were apparently over 400 periodicals devoted to agriculture alone, of which the Stock Keeper and Fancier’s Chronicle was one.

Whether the newspaper appeal did the trick or not we cannot be certain, but Emilie did become a pupil. Born on 11 Oct 1884, she became a pupil after her father died in 1892. She left in 1900 but we know that she visited the School in 1912. She lived in Surrey all her life and died in 1952 unmarried, her probate being granted to her sisters Flora & Alice. As was customary at the time, neither of these two became pupils. It was usual for only one girl (and one boy) of each family to receive a Masonic education although others were assisted in other ways.

We’re turning the heel of the stocking now.

Perhaps as evidence that there may be nothing unusual about individual girls receiving separate support in newspapers to encourage voters, Ada Carter received a similar treatment.

This appeared in Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle on April 07, 1877. Originally published by Robert Bell in 1822 as Life in London, it was a weekly four page broadsheet with an anti-establishment slant, priced 7d. It contained general news but, as its later title might suggest, it became more focused on sport, in particular prize-fighting:

“it was particularly known for its reports on horse-racing, publishing up to date information on schedules and results.” https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/titles/bells-life-in-london-and-sporting-chronicle

Amongst its many contributors was Charles Dickens and so here we have another link with the School!

Ada Carter was born in Nottingham in 1867. In 1864, her father, James Tomlinson Carter, was described as a gentleman who had been promoted to Lieutenant in the Robin Hood Rifle Volunteer Corps. He had a partnership with his father as auctioneers and share brokers, although this was dissolved by mutual consent in 1874. Whether this was because of his health we will never know but he died of consumption just two years later.

As with Emilie, the newspaper support may have encouraged voters in the ballot or it may not. However, Ada also became a pupil and in 1883 she won a prize for General Usefulness. She left later that year “her brother having written for her.” By 1901 her occupation is given as sick nurse and she, like Emilie, visited the School on what was then called Ex-Pupils’ Day, in 1912. In 1915, she married David Alexander Robertson Jeffrey. In fact, the couple took advantage of a new law of consanguinity which had been passed in 1907 as David Jeffrey had previously been married to Ada’s sister Kate. David and Kate had had a son before Kate died and Ada became his surrogate mother until her own death in 1938.

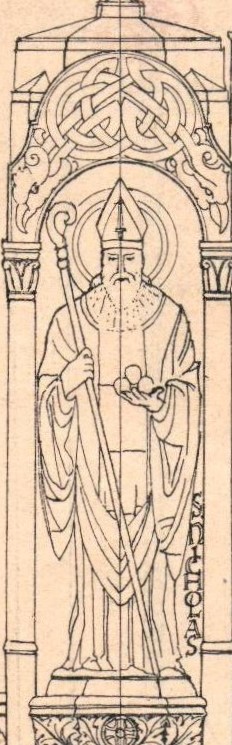

And so we reach the toe of the stocking. Is it a tangerine or a piece of coal? You can decide for yourselves because the last little filler brings us into the 21st century. The Year 7 Reading Group one December were told that they were being taken to see Santa Claus. The aim was to intrigue but they all became very excited at the prospect. Off we set for the Chapel where we found not a jolly figure in red crying “Ho ho ho” but a carved image of Saint Nicholas to one side of the altar connected with the diocese of St Albans in which the School lies.

(Image taken from the architect’s original drawing)

St Nick being the originator of Santa Claus, to say that Santa was in the Chapel was not a lie but some of the girls looked so disappointed that one felt quite guilty. Some of them clearly thought they’d had the piece of coal. Fortunately, another Christmassy occasion made up for it. In Scandinavia on 6th December, children leave their shoes out in the hope that they will be filled with sweets. This same Reading Club had been asked to take their shoes off and leave them to one side. So they didn’t mark the furniture, they were told. Whilst they were otherwise engaged, an assistant surreptitiously filled their shoes with sweets. At the end of the session they were told to retrieve their footwear. There was a pause and then the air was filled with squeals of delight! One little girl came rushing back, eyes shining, to announce the magic that had happened. Well it must have been magic: they hadn’t seen anyone go near the shoes …

The lump of coal my parents teased

I’d find in my Christmas stocking

turned out each year to be an orange,

for I was their sunshine.

William Matthews