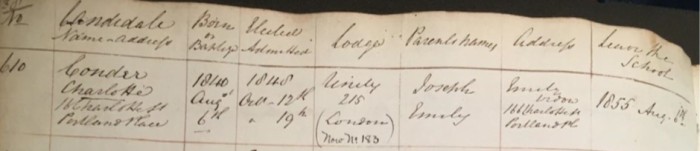

Charlotte Conder, former pupil, was girl number 610 in the registers. She was elected to the School in October 1848.

But, as with so many of our former pupils, uncovering information has such interesting detours into history one almost forgets the little girl of eight placed in the care of Frances Crook, matron, in a school then in St George’s Fields, Southwark.

This particular detour takes in parliamentary procedures, sinecures, pensions, pipes, sojourns overseas and emigrations. Oh yes, and dancing!

Charlotte was born on 6th August 1840 in Blankenberge, Belgium.

English translation by J. Coopman, VVF National Office Antwerp, courtesy of Sanmalc

What is not known is why the family moved to Belgium, which must have happened before 1837 as a child was (still)born there. The family name of Conder, given by several of Joseph’s children (including Charlotte) as de Conde, often with Conder added for good measure, appears to have changed only after Joseph’s death. Research has shown no Belgian or French progenitors in the family, the surname having been traced from 1615 without any change. The gallicisation of the name may have been instigated by Emily – or as she styled herself Emelie – and adopted by some of her children. As Emily and two daughters ran a business teaching languages, it may have added a certain panache to suggest French ancestry. It should also be noted that there was the House of Bourbon-Condé and, although that line ran out in 1830, the implied connection to French royalty wouldn’t have hurt business un peu jot!

Blankenberge, where Charlotte was born, was a holiday resort in the Belle Epoque and frequented by royalty but this was considerably later than the time the Conders resided there. That very English of things – the seaside pier – can be found there, uniquely along the Belgian coast, but that was not built until 1933 almost a century after the Conders so they certainly didn’t go to Flanders to see that.

Joseph had been born in Ipswich (see above for birth of Charlotte) and he married Emily Panton in 1823 in London and neither of those naturally leads to Belgium.

Emily was a minor and married with her father’s permission. Later in life, she claimed to have been born in France as did some of Charlotte’s siblings but there is no evidence for this. Emily and Joseph had eight other children before Charlotte and as all of them, barring Charlotte and Herbert (who died), were born in England, the family cannot have moved to Belgium before 1836 unless Emily kept nipping over the Channel to give birth!

So we make the assumption that the family moved overseas between 1836 and 1837 and they appear in the above document written less than a month before Charlotte’s birth in 1840 and in which all are clearly given as of English birth.

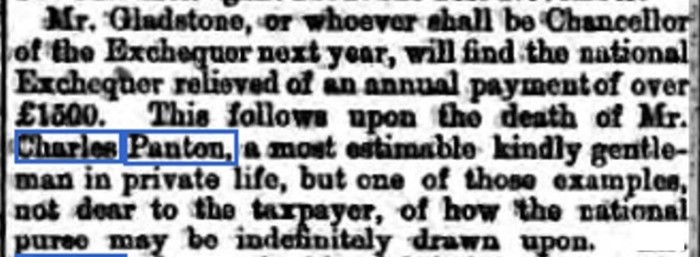

Charlotte’s father and her grandfather, John Pattison Panton, and her uncle, Charles Panton, were all at various times clerks in the Pipe Office. When Charles died in 1882, his obituary may have eulogised him personally but it was fairly savage in its attack on what the paper regarded as civil service ‘snug’ sinecures.

(Obituary of October 14 1882 widely reproduced in provincial newspapers across the country.)

It goes on to say that Charles had had a clerkship in the Pipe Office bought for him by his father in about 1818 and which he had held until 1833 when the Government dispensed with the Office. At this juncture we must digress to look at the Pipe Office which had nothing to do with smoking paraphernalia but everything to do with how the Exchequer functions.

The Clerk of the Pipe was a post in the Pipe Office of the Exchequer responsible for the pipe rolls or ‘the yearly audits performed by the Exchequer of the accounts and payments presented to the Treasury by the sheriffs and other royal officials’ (Wikipedia). The pipe rolls were ‘written on parchment, in the form of two membranes of sheepskin sewn head-to-tail to make up a rotulet … These rotulets were gathered together and sewn at the head, to produce a large roll.’ http://www.piperollsociety.co.uk/page5.htm

The pipe rolls were occasionally referred to as the roll of the treasury or the great roll of accounts. They were the responsibility of the clerk of the Treasurer, who was also called the ingrosser of the great roll and, by 1547, the Clerk of the Pipe.

https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/latinpalaeography/practice12-image.htm

The images above show a pipe roll partially open, with the joins between the parchments visible, and a sample of the palaeography contained within requiring an expert eye to read and understand. And a knowledge of Medieval Latin so if you could just master that by lunchtime, we’ll be home and dry …

In 1824 – not for the first time – a Commission to look into the Pipe Office was set up and Hansard (Vol 24) had the following to say on the matter:

https://books.google.co.uk/books

And this from commissioners who were actually Lords of the Treasury and whom, it might be imagined, would have a vested interest in the status quo.

In 1834, the Pipe Office was dispensed with but, of course, compensation was due to those whose income was so rudely ended in this manner. It came in the form of pensions but

From Charles Panton’s obituary

So Charles received a pension from 1834 which then increased as the more senior clerks died off and their pension seniority came down the line. From 1868 until his death 14 years later, Charles received a pension of £880 pa (the equivalent today of some £30,000) for his role as a board-end clerk which, the post having been abolished almost fifty years before, amounted to a healthy income for no work.

As John Pattison Panton (Charlotte’s grandfather) and Joseph Conder also had positions in the defunct Pipe Office, it must be assumed that they too would have received their compensatory payments. However, as with Charles Panton, their pensions would have ended with their deaths. Joseph Conder died in 1843:

‘In the year 1843, the 17th of the month of September, at eight hours in the morning, before us [James] De Langhe mayor and registrar of the municipality of Blankenberghe district of Brugge, province of West Flanders, appeared [Charles De Langhe and Joseph Everaert] who declared to us that master Joseph CONDER aged 59 years, rentier, born in Ipswich Suffolk, England staying in this municipality, son of Joseph CONDER and Elizabeth JONES, husband of miss Emily PANTON, died yesterday at a quarter past eight in the evening in his house situated in this town.’

The sworn death record of Joseph Conder (trans)

He was actually only eight years younger than his father in law who died the following year.

Evening Mail 29 November 1844

Emily Conder, having been widowed the previous year, had now lost her father so there were big changes in her life. It seems likely, but not certain, that she would have returned to UK after 1843. By 1848, when her youngest daughter Charlotte was admitted to the School, the family address is given as 16 Charlotte St, Portland Place.

Having arrived at the School, and listed as a pupil there in 1851, Charlotte left in 1855 ‘delivered to her sister’ in August. She was to be kept at home ‘to assist in scholastic duties’ and, as she appears in every subsequent census return at the home of Maria Eleanor Conder, later Walton, this is presumably the sister to whom she was delivered.

Nearly all of Charlotte’s siblings left for parts overseas. Three of her brothers went to the USA and became citizens there. Another brother went in the other direction and died in Suez in 1866. The remaining brother became an accountant and stayed firmly in England although, just to keep with tradition, two of his sons emigrated: one to Canada and one to South Africa. Charlotte’s oldest sister went to Australia in the 1850s. She married twice, her second husband being a gold miner in Taradale. She was said to have been able to speak at least 5 different languages and may have acted as an interpreter on the goldfields in Victoria and in the law courts. A propensity for languages clearly runs through the family as the oldest Conder child (Joseph) was editor of the Courier de l’Europe in 1845.

Maria and Charlotte both remained in England and lived in the same household, along with their mother Emily until her death, for the rest of their lives. Between 1861 and 1911, they are consistently in Bristol where they run a school for languages before turning their hands – or should that be feet? – to teaching dancing instead. For at least 30 years, they occupied a house in Park Place, Bristol. This is an area much modernised today but a row of houses that looks to be C19th is possibly the kind of housing they occupied.

(Image from Google Earth street view)

It is unclear from the census returns what kind of dancing was taught by the Conders. It could well have been ballroom dancing or ballet (Degas’ various artworks are entitled the dance class or similar) or a combination.

Between 1891 and 1901, they moved to 18 West Park, Bristol and this remained their home for the rest of their lives. Maria died in 1915 and Charlotte in 1917, the Western Daily Press recording this as ‘Charlotte de Conde; d Jan 3rd peacefully at 18 West Park, Clifton’. She was the last surviving member of her immediate family.

(Image from Google Earth street view)

Her probate, under the name Charlotte Conder de Conde, was granted to Thomas Charles Hubert Walton, secretary, the value given as £245 11s 11d (equiv of approx. £5000).

From Belgium to Bristol, the ballroom or the barre, via Pipe Office or pipe dreams, Charlotte’s story has many interesting side avenues.

(My thanks to SuBa for research work and to Sanmalc for permission to raid her family tree for information.)

While writing an article on K.W. Kronenberger, a teacher of English in Bruges in 1838, I found a letter of Joseph Conder in de Archives of the City of Bruges where Conder lived on that moment together with his family. In the letter Joseph writes that he knows Kronenberger in Bruges for already four years. So it is likely that he moved with his familiy to Bruges in 1834. In Bruges in the nineteenth century there lived a so called English colony. Living in Bruges was cheaper than in England.

LikeLike

Pipe Dreams is fascinating! I had never heard of the Pipe Office.

Is all this done by the School Historian? It is superb. I hope it is appreciated.

LikeLike